At the end of his book Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, journalist and devoted chronicler of Northern Irish history Patrick Radden Keefe shares an indication of Northern Ireland’s persistent struggle. Even though the violence of The Troubles has long since evaporated, he writes, the division between British loyalists and Irish republicans is still strong. As a symbol of Irish independence, supporters have flown Palestinian flags, displaying solidarity with their fellow victims of colonialism.

On October 7, 2023, antisemitic terrorist organization Hamas launched an assault on Israel, killing more than 1,200 Israeli civilians, marking the deadliest day for Jewish people since the Holocaust. In the 12 months since this attack, Israeli forces have pushed through Palestine, into the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, killing more than 42,000 Palestinians and wounding an additional 100,000, with at least half of the victims being women and children; additionally, the United Nations has declared that famine has spread through the Gaza Strip. Suffice to say, it has been an exceedingly brutal and trying year for both Israel and Palestine, with no easy end in sight. So, as the one-year anniversary of the start of this present struggle passes, let’s take a moment to look through the history of this clash, what makes it similar to, and different from, other postcolonial strife, and what that can tell us about the future; what it holds for Israel, what it holds for Palestine, and what that means for the Middle East and the world.

When we think about colonialism, settler societies, and imperial nations, our perspective favors European superpowers. We think of Britain’s disastrous India and Pakistan partition; the wrath of the British army and loyalist paramilitaries in Belfast, Northern Ireland in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s; Latin America or Africa, the warring factions and colonial borders, drawn without the input of the actual citizens of those regions; the imposition of languages like Spanish, French, and English; America’s Trail of Tears, Spain’s genocide in Latin America, and King Leopold’s systematic extermination of Congolese citizens. We think of all of these moments in history, but we rarely think about Palestine.

The conflict between Israel and Palestine has been rife with controversies since its start; the foundation of the modern state of Israel is inexorably entwined with the Holocaust and Nazi-era antisemitism. As we discuss the post-colonial nature of this foundation, it’s important to remain empathetic; the relationship between genocide and the foundation of a Jewish state runs deep. “In my opinion,” Oakdale senior and Multicultural Club President Phoebe Kim expressed, “empathy for other cultures creates opportunities for greater inclusivity and more meaningful connections with those around us. Cross-cultural awareness provides us with perspective on the behaviors of others.” Cross-cultural awareness can also provide a point of comparison, and, maybe, a glimpse into the future; in the lyrics of Sinéad O’Connor, “I want to talk about Ireland.”

“Irish history is transnational history,” Dr. Niamh Gallagher, an Associate Professor of Modern British and Irish History at St. Catherine’s College, Cambridge University, shared, elucidating her draw towards Irish history. “Its global reach always attracted me. What is more fascinating again is its complexity. How could Ireland simultaneously be a Kingdom, and later, a constituent part of the United Kingdom, and yet simultaneously suffer from processes of colonization?” These questions, dichotomies, and struggles make up the fabric of post-colonial Ireland and the Troubles.

The Troubles were an explosion of violence, unrest, and political struggle in Northern Ireland in the second half of the 20th century. In this bloodshed, the epicenter was Belfast; the physical divisions between the Catholics and Protestants bred a culture of violence; Catholics, the majority on the isle of Ireland, were a minority in Northern Ireland, experiencing broad strokes of discrimination at the hands of Protestants and loyalists, who supported the crown’s attempts to hold their imperial claims in Northern Ireland. There were a plethora of Paramilitary organizations, infamously the Irish Republican Army (shortened to the IRA), a group of staunch Irish republicans, and their violent provisional wing, known simply as the Provos. The IRA, over decades, launched a barrage of attacks on the British; from the 1960s until the 1990s, the Provos’ nearly 500 bombing campaigns in London alone resulted in 50 deaths.

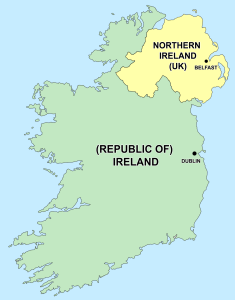

Conflict in Ireland, much like conflict in Palestine, originated years before the most notorious outburst of violence. The Irish War of Independence, in which republicans attempted to drive British forces off of the island, ended in 1921; it resulted in the Partition of Ireland, which went into effect on May 3, 1921. This division, authorized under the Government of Ireland Act of 1920, split Ireland into two sections: the southern, independent Republic of Ireland, and the UK-controlled Northern Ireland. “The Irish Revolution is the name given to the series of events that took place roughly from 1912-1923 that led to the partition of Ireland (under the Government of Ireland Act 1920),” Dr. Gallagher expands. “The granting of a measure of independence (i.e. the creation of the 26-county Free State, which preceded the Irish Republic) and civil war (firstly within the UK from 1919-21 and then within the [newly formed] Free State from 1922-23). It was a contest over various political rights, and some of the most significant centered on constitutional rights.”

The partition of Ireland, Dr. Gallagher continues, “cannot be explained in a simple sentence.” (For more information, Dr. Gallagher suggests “having a look at my [London Review of Books] review of Charles Townshend’s book The Partition [or reading] Robert Lynch’s book and Cormac Moore’s.”). This closely resembles the complexity and political makeup of the partition of Palestine, which was similarly organized by the colonial wing of the British Government. That agreement attempted to curb aggression between the indigenous Arab population of Palestine and the British-and-American-allied Jewish population of the newly established State of Israel by formally defining its boundaries. Ireland and Palestine share an experience as the victims of British colonialism, and both countries, burdened by the psychological and often physical repercussions of that imperialism, turned to violence as a rebuttal. As to say, the origin of these terror organizations (the IRA and Hamas) is the result of colonial violence, not the other way around. The way forward, then, must be an end of the active aggression by the imperially backed power.

In Northern Ireland, that’s exactly what happened. After years of strife—bombings, shootings, fights, riots, and public massacres—the IRA began to shift to a more political position. It was a controversial move, with many IRA members resenting the leadership for finding compromises with the British government, who they viewed as the enemy. Ultimately, this is what is bound to happen in these sorts of conflict: compromises always have to be made in the name of peace, even to the chagrin of those who sacrificed a great deal to achieve their goal. Of course those staunch republicans, who fought tooth and nail, often to great personal danger or harm, for a United Ireland, would be disappointed that the political compromise that was made allowed the British to maintain their control of Northern Ireland. There were many roadblocks too; there were many times where the IRA was more than ready to make peace deal or ceasefire with the British government but their leadership threw it out, because of lack of respect for the cause, a general apathy towards the conditions in Northern Ireland, or an inexorable belief in the British Empire’s justifications for colonialism. It was only once those ideas were disbanded, thrown aside, aged out, and rendered antiquated that peace was able to be made, and more importantly, maintained. Was everyone happy? Of course not. Was everything fixed in Northern Ireland? No. But was general amiability found? Yes.

You can still see the remnants of the Troubles in Belfast: there are physical walls still dividing the Catholic and Protestant communities, which are, even now, largely segregated. There’s still an air of discomfort, discontent, and animosity in these regions. These populations which, now at least a generation removed from the peak of the conflict, still have to reconcile their identities with the outcomes of the Troubles. This, disappointingly, depressingly, and realistically, is what a peaceful future for Israel and Palestine looks like: a tense, uncomfortable, and imperfect solution, with the ripples of imperialism still being felt, the scars still healing, and the physical remnants of the battles—the wrecked buildings in Gaza, the settler societies in the West Bank, the bombs in Jerusalem—still visible, even if the buildings have been rebuilt. The steps towards that, at the very least, peaceful future remain unclear, but the first step has to be a permanent, effective ceasefire, a respect of Palestinian rights, and an active dedication to a lasting, amicable solution.

Editor’s note: This article is a brief overview of one perspective on the Israel-Palestine conflict and does not claim to be a definitive history of events. While accuracy and objectivity were strived for, there are bound to be historical inaccuracies in this text. Please practice due-diligence and do your own research before forming your own opinion.