In the past few months, generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) has taken the world of entertainment by storm. Conversations between the formerly striking writers and the Hollywood studios proved that this issue is much bigger now than they had previously expected. While this battle (won by the writers after last week’s contract negotiations) has been halted for now, it’s important to remember why it was important in the first place.

Art is fundamentally the expression of the human condition characterized by one person, an emotional subjectivity which the objective AI lacks. As Ms. Margaret George, an art teacher at Oakdale High, explained: “I do think that [AI] lacks the person. Obviously AI doesn’t have personality. I think that it takes from the human element that is art, because with AI, it’s programmed to do a certain thing in a certain way. I think that it lacks the human error and human experience. I think that a lot of artists create art as an outlet, [whereas AI does it out of a system.]”

The system of AI is based on previously available information. Mr. Brian Ranallo, a CTE teacher at Oakdale High, demystified the process this way. “AI is machines getting fed lots and lots of data,” he said, “and then the [machines’] algorithms learn how to interpret that data and then make predictions on what the data is for future reference.”

In this regard, generative AI (the kind of AI that creates material from the system Ranallo described) could even be viewed as plagiarism. While it may not be using the same text or the same phrasing, its regurgitation of style as purely literal, without being processed through another individual’s inverted prism of worldview, is a violation of the artist’s individuality.

Ranallo and George disagree with this sentiment. Ranallo views the AI’s information synthesis as sufficiently interpretative to be separate from the original material, and George expanded on this, stating that, “it’s inspiration not plagiarism. If you fed it all of the French impressionist paintings or all of Van Gogh’s paintings,” she argued, “and it created a piece inspired by that, I don’t think that it’s exactly plagiarism. I think [it’s] gaining the knowledge and inspiration in that style and turning it into something new.”

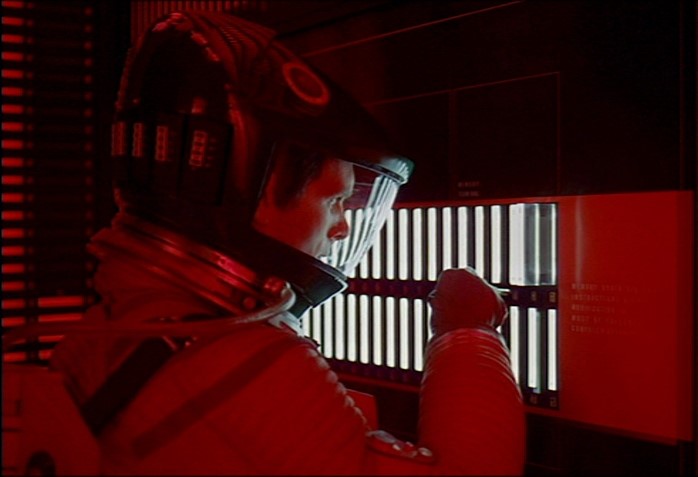

It could be argued that the recreation of style without processing through the human mind is merely impersonation, which holds almost no artistic value. To use a famous example, earlier this year, there was a viral trend in which people recreated their day through the, “style,” of a Wes Anderson film. There were even viral AI versions of this trend, projecting Anderson’s aesthetic onto Star Wars or Lord of the Rings.

What these mere impersonations miss is the depth of Anderson’s filmography; Anderson’s style is, itself, an appropriation of filmmakers like Jacques Demy or Hal Ashby filtered through his own philosophy and worldview. Anderson’s style is not an objective aesthetic or a distinct manner of speaking, but the juxtaposition of his postcard-pretty pictures on broken characters, who are usually depressed or grieving. Of course, any AI going through his films would not catch this human emotion, and, therefore, what it spits out would lose the meaning.

As the Writers Guild of America reaches their agreement with the Hollywood studios, which includes restrictions on the usage of AI in Guild-backed projects, it’s important to remember that while AI is the future, its inevitability does not negate its inhumanity. As George puts it, “[I told my students,] ‘why would I want that? Why would I want a computer generated photo? I want to see what you are seeing in your day-to-day life, I want to see through your eyes.’”

While AI-generated material could be art, and while it may not or may not be plagiarism, there’s, as George put it, a bigger problem: “It’s [just] not interesting.”